Where data is concerned, it’s no longer business as usual. A nascent wave of wokeness in digital culture has made its way into public consciousness regarding how central the flow and analysis of personal data is to socio-economic and political life in an increasingly digital age.

Watershed events like the Cambridge Analytica scandal, the infamous Equifax breach, and the Microsoft breach have all only fast-tracked the arrival of a horde of legislation aimed at regulating data privacy.

At the time of researching this article, 162 countries have enacted omnibus data privacy laws, most of which are modeled on the GDPR. Sectoral laws like the CCPA/CPRA also contribute to the jurisprudence on data privacy.

Another offshoot of the meteoric rise in this awareness is the now-lucid gulf between what users consider permissible and what companies actually do with their data.

Cue in the legislature. With the CCPA/CPRA and the GDPR united by purpose in placing users more in the driving seat of their digital destiny, an assessment of these regulations will go a long way in providing a clear roadmap toward compliance, especially for organizations that may be operating globally and online.

In this article, we take a cursory look at areas of divergence and what this means for your compliance objectives:

A quick glance at the laws

The General Data Protection Regulation (EU GDPR)

The granddaddy of data privacy regulations, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) has been the gold standard for data protection throughout the European Economic Area (EEA) including countries in Europe (the EU) since it entered into effect on the 25th of May, 2018.

The GDPR is currently recognized as the most comprehensive piece of legislation on data privacy globally, as it covers data controllers and processors (including public bodies).

While the GDPR isn’t an American invention, the global ramifications of data processing meant that prior to the arrival of US state laws on privacy (the US is yet to establish a federal law on privacy), companies had to document and, to an extent, be held accountable for collected data.

The California Consumer Privacy Act of 2018 (The CCPA)

Renowned as one the world’s largest subnational economies and a liberal powerhouse, a data privacy law that mirrored the state of California’s socio-economic heritage was long overdue.

The California Consumer Protection Act (CCPA) of 2018 marked the US’ debut in data privacy legislation. Branded as GDPR ‘lite’ in some quarters, it came into effect on the 1st of January, 2020.

When weighed against its European counterpart, the CCPA is less stringent. Still, the California-bound legislation remains the strictest consumer privacy protection law in the United States.

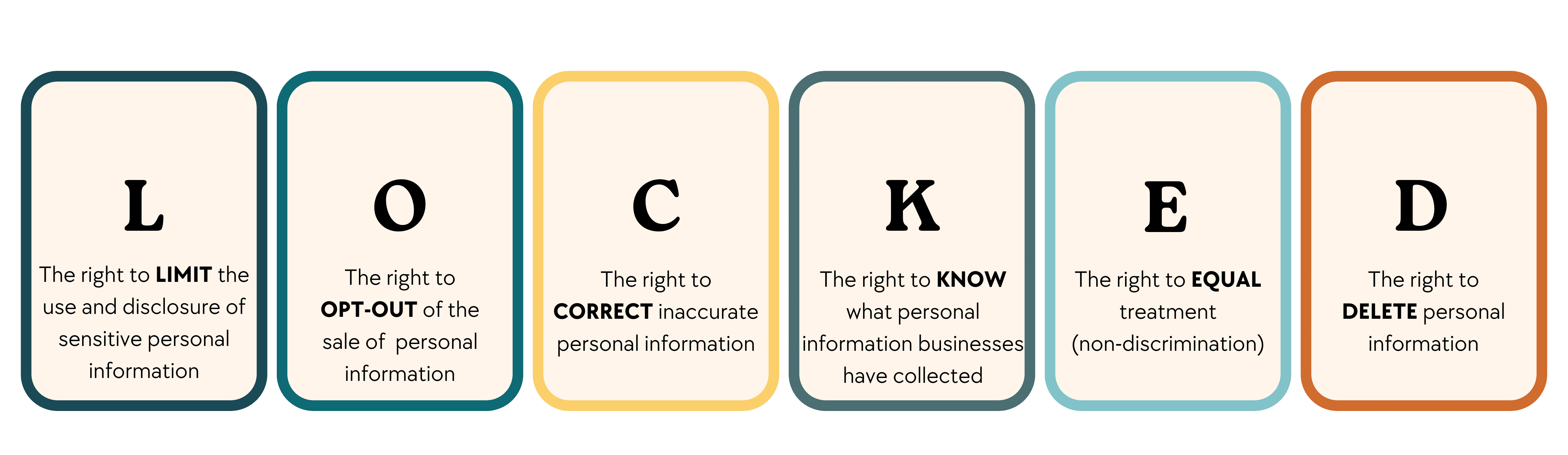

The CCPA confers certain rights on consumers which the act itself reduces into the mnemonic, ‘LOCKED.’ The CCPA ‘locks’ (forgive the pun) in:

- L – The right to LIMIT the use and disclosure of sensitive personal information collected about them.

- O – The right to OPT-OUT of the sale of their personal information and the right to opt-out of sharing their personal information for cross-context behavioral advertising.

- C – The right to CORRECT inaccurate personal information that businesses have about them.

- K – The right to KNOW what personal information businesses have collected about them and how they use and share it.

- E – The right to EQUAL treatment. Businesses cannot discriminate against consumers for exercising their CCPA rights.

- D – The right to DELETE personal information businesses have collected from them (subject to some exceptions).

In August 2020, the Final CCPA Regulations were approved, offering additional requirements and clarifications for the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA). Subsequently, on March 15, 2021, more regulations were approved to further nudge businesses in line with new realities and provide consumers with additional protections.

The California Privacy Rights Act of 2020 (The CPRA)

The last quarter of the year 2020 heralded the passing of “the Proposition 24” by Californian voters, reinforcing privacy rights with the California Privacy Rights Act (“CPRA”). The CPRA was a ballot initiative given approval by Californian voters on November 3, 2020. It significantly amends and affirms the California Consumer Privacy Act of 2018 (“CCPA”).

Branded as “CCPA 2.0” in some quarters, the CPRA entered into force on Dec 16, 2020, with the vast majority of the provisions amending the CCPA not taking effect until Jan 1, 2023.

The Sacramento County Superior Court pushed enforcement of the CPRA regulations from July 1, 2023 to March 29, 2024, in a last-minute decision on a complaint filed by the California Chamber of Commerce.

The CPRA is more of an amendment than a replacement. It revises certain provisions of Title 1.81.5 of the California Civil Code (also known as the CCPA) and layers on additional obligations for businesses and privacy rights for Californian consumers.

GDPR vs. CCPA & CPRA - Comparison

For most organizations, navigating the regulatory maze of the GDPR, CCPA & CPRA can be like solving a Rubik’s cube while standing on one feet. So any steps towards compliance should begin with a clear grasp of the spirits and letters of the laws.

This is the crux of this guide. We’ve compiled this quick GDPR CCPA comparison to give you a bird eye view of how each law sets about achieving its data privacy objective.

What principles are common denominators to each law? What sets them apart? We analyze these queries along the lines of the below criteria:

GDPR vs. CCPA & CPRA:

Scope of application

Similarities:

⟶ The GDPR draws parallels with the CCPA and CPRA in terms of who it applies to. Both apply to natural identifiable persons. Notably, there is a divergence in the terminology. The GDPR uses the term “data subjects” while the CCPA & CPRA refers to “consumers”, and defined as natural persons residing in California.

⟶ The class of “personal data” also captured within the context of both laws is one and the same: any information that could be linked (directly or indirectly) to any individual.

The GDPR and the CCPA as amended by the CPRA also exclude the processing of personal data by non-profit organizations from its regulatory oversight.

Processing for purely personal or household purposes, or for purposes of law enforcement or national security are also excluded.

Differences:

⟶ The GDPR has an extra-terrestrial scope. This means it offers a blanket protection to data subjects with a presence in the EU irrespective of their nationality, place of abode, or whether the data processing activity taking place in the EU.

Tellingly, the CCPA & CPRA are limited in scope to California residents (yet binding even if they are temporarily not within the state) and entities with California as their place of business.

⟶ Another salient feature of the GDPR that makes it so comprehensive is its application to data processors and controllers including public bodies. The CCPA on the other hand fails to bring public bodies under its regulatory remit.

⟶ There’s also a divergence in terminology. GDPR recognizes “data controllers” and “data processors” while the CCPA & CPRA refers to “service providers” and “for-profit businesses.”

The CCPA also covers “contractors” and “third parties” who are in receipt of data, whether in performance of a contract or not.

GDPR vs. CCPA & CPRA:

Key definitions

Similarities

⟶ Accountability for non-compliance falls at the feet of two parties. The GPPR lays down rules for “controllers” and “processors” regarding whether and how they process data. They’re the CCPA/CPRA equivalent of the “businesses” and “service providers.”

⟶ The concept of “Personal information (PI)” takes similar interpretations.

For instance, the CCPA adopts a broad definition of personal information as one that relates to, identifies, describes, or is reasonably capable of being linked, directly or indirectly, with a consumer.

It then proceeds to draw up a laundry list of information including:

- Identifiers including name, address, unique personal identifier, IP address, account name, SSN, driver’s license number, passport number (the GDPR also stipulates this);

- Personal information described in Section 1798.80(e) of the CCPA;

- Protected classifications under California or Federal law;

- Commercial Information;

- Information on internet activity;

- audio, visual, electronic, thermal, olfactory, or related information;

- Geolocation information;

- Employment-related/professional information; and

- Biometric information, along with a host of other information or inferences drawn from any such information that may be used to profile consumers.

The CPRA revises the CPPA, including “sensitive personal information” on this list and going further to define it as any online identifier that discloses sensitive personal data or biometric information for the purpose of profiling the consumer.

In a similar token, the GDPR defines “personal data” as information relating to an identified or identifiable person by reference to an identifier or to anything that relates to their physical, physiological, mental, genetic, economic, social, or cultural identity.

In effect, where an EU-resident organization processes the personal information of California Residents, they can be both a data subject and consumer simultaneously.

All three laws also exempt “anonymised data” from regulatory scrutiny, especially when such data has rendered the data subject or consumer practically unidentifiable.

Difference

⟶ The CCPA lays down a caveat to what constitutes “personal information.” Publicly available information, de-identified, and aggregated information are not deemed to be personal information, which means businesses can sell, collect, or retain them without disclosure.

The CPRA adds lawfully obtained information or information obtained in the interest of the public to this list. Effectively, publicly available information disclosed by federal, state, local government records, or the consumer themselves can be processed without disclosure.

Conversely, GDPR permits only the retaining, collecting, and selling of anonymous data without the need to disclose them.

⟶ The CCPA has for-profit businesses as the focus of its jurisdiction. According to the CCPA, “Businesses” are defined as “for-profit” organizations in California that collect personal information (either online or offline), dictate the purpose and means of processing, and:

- Earn a gross annual revenue of over $25 million for the preceding calendar year;

- Buy, sell, or share the personal information of 100,000 or more California residents or households; or

- Make 50% or more of their annual revenue from selling or sharing the personal information of California residents.

In GDPR parlance, the definition of “Data Controllers” broadly covers a legal person, both private or public entities, public bodies, or any other organization who solely or jointly determine the purpose and means of processing, regardless of their revenue.

⟶ “Data processing” under the GDPR spans the entire range of collecting consent, serving notices to data subjects as to the purpose for collection, method of processing, and their data rights, and the deletion of their data.

The CCPA delineates data activity along three touch points in the consumer data lifecycle to wit:

- Collection: Obtaining data from consumers, vendors, and third parties

- Processing: Any act carried out in the exploitation of the data for commercial gain.

- Selling: The transfer of data to another organization.

GDPR vs. CCPA & CPRA:

Legal basis

Similarities

⟶ The GDPR and CCPA (as amended by the CPRA) codify certain justifications for the processing of data namely:

- User consent;

- Processing only to the extent required to perform or fulfill a contract;

- Compliance with a legal obligation;

- For academic, scientific, historical, or statistical purposes; and

- In defense or pursuit of a legal claim.

Both laws also furnish controllers and businesses with directives on:

- What constitutes valid consent: Consent must be freely given, specific, informed, and an unambiguous manifestation of the data subject or consumer’s wishes; and

- How to validly obtain consent: The CCPA in its Guidelines for Prevention and Regulation of Dark Patterns launched in 2023 outlawed “dark patterns”. This involves the manipulation of design patterns in UI/UX to subvert user autonomy or influence user decision-making, often to their detriment.

⟶ Both laws also tighten the screws on accountability by demanding explicit consent and specific notices in processing a special category of data.

Differences

In the GDPR, the threshold for valid consent is a clear, affirmative act of agreement by the data subject, either through a written statement made electronically or given orally. However, the CCPA demands notices displayed to the consumers either before or at the collection point.

GDPR vs. CCPA & CPRA: Obligations

Similarities

⟶ The GPDR and the CCPA as amended by the CPRA allow for the transfer of personal information, provided the transferee has a similarly adequate level of data protection.

⟶ The duty to keep a record of all processing activity is also common to both legislations. The CCPA further specifies maintaining records of verifications of requests as part of such records.

⟶ Both laws also impose strict liability. The activity of data controllers and processors in collecting and processing data imposes an obligation to ensure third parties/data recipients are able to fulfill consumer requests and are also compliant with the laws.

⟶ In the spirit of integrity and confidentiality — principles both laws recognize — the GDPR and CCPA/CPRA state that reasonable security measures must be taken to protect data. This is also to be exercised alongside the duty to immediately notify the relevant supervisory authority in the event of a breach. In the case of the CCPA/CPRA, the AG is to be informed of the breach once a single breach is found to affect 500+ California residents.

⟶ Data controllers under the GDPR and businesses under the CCPA/CCRA are required to abide by purpose limitation and accuracy principles and to rectify inaccurate or incomplete information.

They are also obligated to implement security measures and best practices and notify the authorities in case of a breach. Service providers and data processors are further compelled to only use personal information shared with them in a manner that is consistent with the business and data controllers’ obligation and the contractual agreement binding them both.

Differences

⟶ The GDPR stipulates the performance of a risk identification assessment protocol called the DPIA (Data Protection Impact Assessment). The CCPA, on the other hand, requires annual audits in risky industries. However, this has now been amended by the CPRA, as the AG of California is now vested with the jurisdiction to:

- Consult with the public and stakeholders in mandating businesses whose processing activities are of high risk to perform annual cybersecurity audits; or

- Submit an internally conducted risk assessment to the CCPA periodically.

⟶ The GDPR also requires the performance of a DPIA and close consultations with supervisory authorities once there is a change to processing operations or technology that may be high-risk. The CCPA does not provide for such; instead, it requires risk assessments on an annual basis.

⟶ Another innovation of the GDPR is the obligation to appoint a Data Protection Officer (DPO) by data controllers or data processors. This is notably absent in the CCPA/CPRA.

Under the GRPR, processors and controllers are obliged to designate a single DPO who must be easily contactable by data subjects. This is true for public bodies that process data or where a certain class of data is processed in large amounts. Such provisions are absent in the CCPA/CPRA.

GDPR vs. CCPA & CPRA:

Data Subject Rights

Similarities

⟶ The right to object is expressly provided for in the GDPR with provisions for limitations in certain instances.

The CCPA and CCPR’s “right to opt-out” of sale (of consumer data) captures the legislative intent of this right, with its own exceptions.

To reinforce this, the CCPR compels businesses to, at the consumer’s request, limit processing to only as far as is necessary for providing services. This aligns with the GDPR’s right of data subjects to withdraw consent. Under both laws, data subjects and consumers are required to be informed of their right to object.

⟶ Disclosure rights are central to the CCPA and CPRA, particularly on businesses that sell personal data. The data subjects’ right to access in the GDPR is of the same persuasion as these disclosure rights and can be likened to the “right to know.” Both laws compel the use of identity verification mechanisms to verify consumer requests.

⟶ Right to Erasure/”the right to be forgotten” is an invention of the GDPR. Laudably, the CCPA and CCPR drew inspiration from this provision to offer consumers the right to delete personal information via writing, orally, or other electronic means — and at no cost. They must also be informed of this entitlement in both laws.

⟶ Tellingly, the GDPR’s “right to be informed” is of a similar character to the “right to know” in the CCPA and CPRA.

⟶ The GDPR and CPRA commit to data portability rights, recommending a readily usable format that eliminates friction in the transmission. Given that anonymous data is not covered by both laws, it does not constitute ‘portable’ data.

Differences

⟶ A case can be made for constructing a “right against discrimination” from the wording of the GDPR. However, there is no express provision in this regard. In contrast, the CCPA and CPRA expressly outlaw businesses from discriminating against consumers in the exercise of their rights.

⟶ As it concerns the right to be informed, the GDPR imposes a duty to inform data subjects about using automated decision-making or profiling at the point of collection. They must also be informed about possible repercussions of not providing data or if there is an adequacy decision or not. Besides the “right to know,” no such provisions exist in the CCPA/CCPR.

⟶ The right to object, according to the GDPR, includes informing data subjects on how to exercise their rights. The CCPA deploys a “Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information” button to be made available by the business to enable consumers to make their objections known.

⟶ The GDPR limits the right of access to certain conditions. For one, the right must not encroach on the freedom of others. Data requested must not include trade secrets, and requests must not be manifestly unfounded, repetitive, or excessive. There is no such limiting provision in the CCPA/CCPR.

A timeline is also prescribed. Under the GDPR, all requests, including deletion and access requests, must also be handled within one month from the lodging of the request (typically calculated from the day after a request has been sent), while the CCPA and CPRA provide a timeframe of 45-days for the same from the date of receipt of the request of access or deletion.

In exceptional circumstances (for instance, where there is an unusually high number of requests,) the deadline is renewable by another two months.

The CCPA and CPRA set a more conservative 45-day deadline, renewable by another 45 days which must be communicated to the consumer.

Under the CCPA and CPRA, businesses are to, within 10 business days, acknowledge receipt of the request for deletion and inform third-party service providers/contractors of their obligation to delete.

As a caveat, however, the CCPA and CPRA obligation to delete only so far as the request is directly made to the business, not to a service provider. This is because Service providers and contractors are accountable to the business they receive data from, not the consumer per se.

GDPR vs. CCPA & CPRA:

Enforcement and remedies

Similarities

⟶ Administering monetary fines is an enforcement mechanism common to both the CCPA/CPRA and the GDPR with a host of aggravating and mitigating factors like:

- The nature and seriousness of the infringement

- Whether the offender is a repeat offender

- If any actions were taken to remedy the infringement

- Whether or not the offender was wilful or persistent in their misconduct.

⟶ Notwithstanding the different supervisory authorities, under the GDPR and CCPA/CPRA (the Data Protection Authority and the AG of California/California Privacy Protection Agency), both enjoy similar jurisdiction to investigate possible violations.

They’re also imbued with corrective powers to make and enforce orders and educate the public on data protection best practices.

Differences

⟶ The GDPR allows member states to appoint their supervisory authority. The CPPA has the Attorney General of California and the California Privacy Protection Agency as its supervisory authority.

⟶ Both the CCPA/CPRA and the GDPR pack some teeth in redressing violations. The CCPA doesn’t place a ceiling on monetary penalties. But on average, monetary penalty can be up to $2,500; or $7,500 if there is proof of intention or involvement of a minor of less than 16 years old.

The GDPR’s monetary penalty is 2% of global annual turnover or €10 million, whichever is higher, or 4% of global annual turnover or €20 million, whichever is higher.

⟶ The administration of fines under the GDPR is immediately binding.

CCPA violations are redressed by way of a civil action brought by the CPPA. But first, there is a 30-day cure period within which to remedy the default and have the fine overturned. This ‘window of grace’ now no longer exists due to its repeal by the CPRA.

⟶ Regarding remedies, actions brought under the CPPA are time-bound. No action shall be commenced later than 5 years from the date of the violation. Such a provision is non-existent in the GDPR.

⟶ Damages awarded as a result of CCPA violations are to be within the range of $100 to $750 per consumer or damage suffered, whichever is greater.

Wrap up

Just as any in-depth gdpr ccpa comparison must highlight the policy leanings of the GDPR towards “privacy by default,” we can also percieve the CCPA & CPRA to be a lordly intercessor for consumers, putting businesses and service providers to the task of accountability and full disclosure.

Consequently, if legal basis is the key to unlocking GDPR compliance, then the same is true of transparency especially regarding how user data is used, shared, or sold in the CCPA & CPRA.

Their shared boundaries and differences notwithstanding, these two leading pieces of legislation will continue to drive even more legislative action. More states in the US will take a page from the CCPA’s playbook, whilst the GDPR continues to provide the global benchmark for standard regulation on data privacy and security.

Peter Oladimeji

Peter is a Nigerian-based attorney with a bias for data privacy & intellectual property. When he's not exploring the curiosities of the in-betweens, he's recoiled in his couch, reminiscing the Manchester United of his childhood, or lost in maladaptive daydreams of the club’s return to former glories.

- Peter Oladimeji#molongui-disabled-link